‘Second-class citizens:’ Hard-of-hearing employees frustrated by lack of accessibility in remote and hybrid working

If you think the enforced remote-working set-up of the last 16 months has been tough, multiply that by a thousand, and you’ll be somewhat closer to what a deaf or hard-of-hearing employee has experienced.

The bulk of employers have failed to provide enough of the accessibility tools required for communication between its hard-of-hearing and hearing staff in remote-working setups, according to spokespeople for those communities. These tools, which include video captioning and digital interpreter services — so readily accessible in an in-office environment — have been missing in remote-working environments, where its already far harder to rely on lip reading and sign language.

The result is that these individuals have felt isolated and sidelined. Some have even quit due to the conditions.

And with hybrid-working models set to become a permanent fixture across the entire business world, employees with additional accessibility needs fear it may worsen if left unchecked.

Naturally, frustration levels have reached boiling point. Nathan Gomme, executive director at New Mexico Commission for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing, said he has witnessed people become “distraught” at the lack of support they receive. “[They] felt like they [the employer] didn’t care about their access needs and they didn’t care about them,” he said. He added that often staff have felt like “second-class citizens” as a result of their treatment.

The human interaction and camaraderie of the office has been sorely missed by many over the last year. For the hard-of-hearing, the absence of in-person meetings and conversations has been felt perhaps even more keenly as they’ve struggled to lip read, use sign language, access interpreters in time for video meetings. HR departments are proactive at providing accessibility tools for in-office meetings, due to the Americans with Disabilities Act Standards for Accessible Design compliance rules, but have been slow to ensure they’re replicated in remote set ups, according to the same spokespeople.

“When we have difficulty in a meeting because we only get part of the information because we miss so much, it can impact the company directly if there are serious misunderstandings,” said Joe Duarte, co-CEO of InnoCaption, a mobile app which offers real-time captioning of phone calls. “Many times, we may feel embarrassed to ask for help.”

That also causes a drop in self-esteem and makes people feel isolated which in turn affects their work and productivity, said to Duarte. “Often those with communication challenges due to lack of accessibility tools and options such as captioning [on video calls] or interpreters, may be given projects or assignments that don’t require much interaction with team members. This is always sensed by us and it always has a negative impact on morale and on productivity,” he added. “Providing accessibility and equal access to communications to allow deaf and hard-of-hearing employees to work at the same level as their hearing peers is essential in any organization.”

Back in March 2020, everyone’s home working set-up was a mess. Home wifi connections bent under the strain of back-to-back video meetings, causing painful frozen-screen moments and disjointed conversations. For junior staff (at some major global businesses), it could be a ritual in humiliation as colleagues were suddenly transported into their, often shared, apartments. Tales have since emerged of employees doing presentations with their laptops precariously balanced on top of ironing boards (that naturally, collapsed mid call), or perched on the end of their beds, due to lack of space. Others have struggled to juggle full-time jobs with kids bursting in on video calls with colleagues and clients, causing general mayhem. It was a difficult time.

Yet since those first few months employers have invested in getting their workforces set up with more sophisticated home workstations, meaning a lot of those earlier glitches have been gradually smoothed over and laughed off with the joyous luxury of hindsight.

But that’s not the case for deaf and hard-of-hearing community. While some businesses have made efforts to apply some level of accessibility for hard-of-hearing employees in remote-working and hybrid set-ups, most haven’t come close to providing the tech investment needed nor the training of bosses and colleagues in how to cater for people with additional accessibility needs, according to the same community spokespeople.

Technologies still don’t have the display and control flexibility that deaf and hard-of-hearing people need to see the lips of the people speaking and “pinning” interpreters next to the speakers is not always an option.

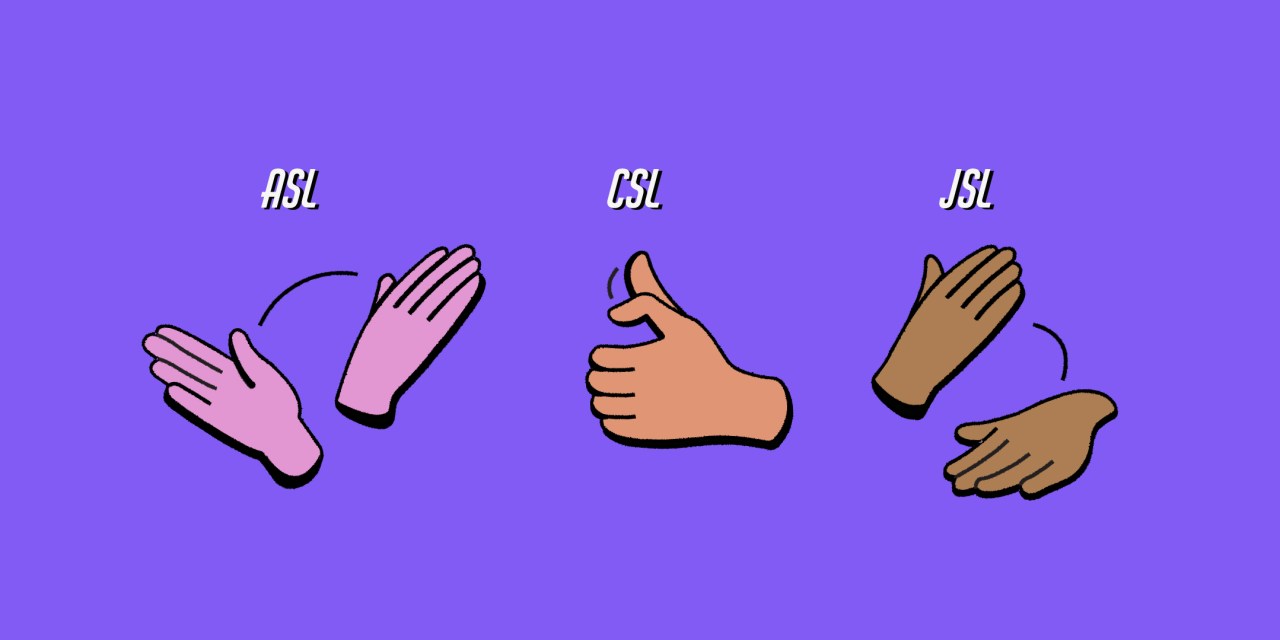

Tech platforms like Google do have products designed for hard-of-hearing communities. But disparity between remote conferencing platforms like Zoom, Google Meet, Microsoft Teams and Cisco Webex have caused issues, said Eric Kaika, CEO at U.S. nonprofit TDI For Access. “Few of them allow third-party captioners to join and provide transcript services, while others may have an ASR-only [automatic speech recognition] captioning feature, which isn’t always accurate.” And some of them actually block these services due to security reasons, he added.

There is even a curious amount of red tape when it comes to what video and chat apps employees can use at home, which are useful (like Marco Polo and Glide for instance) for those using sign language to make it easier to communicate while working — if they’re not approved by organizations’ IT departments, employees are banned from using them. That’s created additional frustrations, Gomme added.

“A workplace that is top-to-bottom inclusive and accessible is more productive and appealing to the general community,” said Gomme. “Workplace productivity improves, retention improves and recruitment improves when a workplace is accessible. Remote work is very attractive right now and when done right, a person with a hearing loss is just as effective and productive. When the culture of an office is inclusive that also means that a person calling a company or agency will have a better result as well.”

A total 48 million people in the U.S. alone have some form of hearing loss, according to TDI Access. And while progress has been made since the onset of the first lockdowns, there is a long way to go before needs are fully met in remote and hybrid-working setups, these spokespeople claim.

Better equipment, such as additional monitors to provide more screens for interpreters and move captions for multiple speakers can go a long way to solving the problem, according to Gomme. And IT teams need to look beyond the immediate remote-work employee needs such as VPN (virtual private networks) and documenting software, and learn about the various programs designed for access so they can ensure they’re not blocked for staff that need them.

“Having a protocol for discussions [during meetings], shared screens, pinning and interpretation procedures mean the burden is not on the employee,” said Duarte.

Kaika hopes more companies can make accessibility part of the company’s core values, and for experts to be brought in at the design phase (of hybrid setups) which will give organizations an edge when it comes to attracting and retaining all talent with a mix of accessibility needs.

“If they [employers] don’t prioritize accessibility at the very beginning, then they’ll always play catch-up and having to retrofit or sunset their applications,” he added.