How employers are designing neurodiverse workplaces

About 20% of people are neurodivergent, meaning they have autism spectrum disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, dyslexia or another learning or mental health difference. In other words, there are most likely at least a handful of people in every workplace who might identify as neurodivergent.

Accommodating neurodiverse employees in the workplace is necessary for employers who want to have inclusive workforces. One major way to achieve this is considering the design of an office in a way that fits everyone’s needs.

Global design, architecture and engineering firm HOK identified four trends related to neurodiversity that will reshape the workplace between now and 2030, including technological developments, demographic developments and environmental changes, a focus on health and well-being, and the fast pace of change in organizational business models.

Both the Americans with Disabilities Act and the U.K. Equality Act consider neurodiversity as a disability and help ensure neurodivegent people have proper accommodations at work. The British Standard Institute also just released guidelines for how to address neurodiversity, which will also hopefully ensure even further inclusivity.

“Five years ago, very few in the architectural world even knew what neurodiversity was,” said Kay Sargent, senior principal and director of WorkPlace at HOK. “There is an amazing wave that is starting to flow now about information regarding neurodiversity. We focus on trying to create environments that not only welcome people in, but make them feel productive, included and give them an equitable experience when they’re there.”

Judith Carlson, workplace strategy manager at interior design firm Ted Moudis Associates, said that this kind of inclusion has always been important, but it has been brought to the forefront of office design since the pandemic made us all rethink working in the office.

But designing an office to be inclusive of neurodiversity doesn’t mean simply changing a few quick things. It requires a true understanding of the needs of these individuals with an intentional approach. Sargent explained that neurodivergent workers tend to be either hyposensitive (a dulling of the senses) or hypersensitive (sensory overload) to their environment, which means an office design needs to be inclusive of both categories and offer different options.

“All of us tend to have different sensory thresholds to all that different stimulation that is coming at us,” said Sargent.

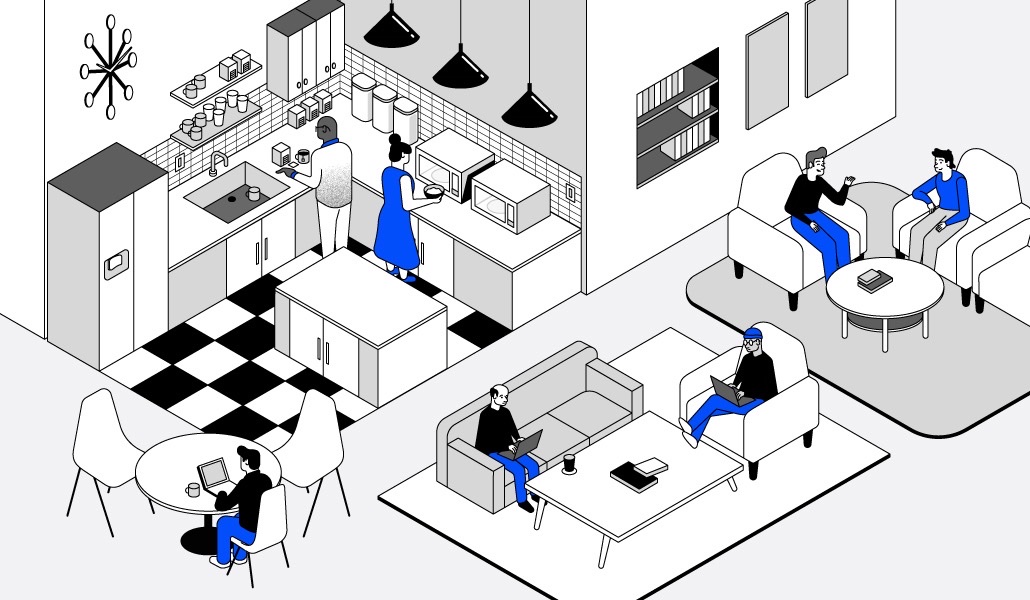

At the root of designing to include a neurodiverse workforce is giving people options, choice and control. Designers consider things like acoustics, lighting, temperature, space and textures, and how to mix and match these things so there is something for everyone.

Sargent said at HOK, the practice of combining different work environments in one office is being rolled into most projects, whether or not a client asks for it specifically.

“Being able to have that flexibility is key,” said Cait Russell, director of the Neurodiversity Employment Network: Philadelphia. “We heard about the impacts of the sensory environment on neurodivergent employees. It can be a big barrier in the workplace, whether it’s loud noises or being too close to the kitchenette.”

“Employees can create the workspace that’s best for them based on the options they have available,” she continued.

That might mean that employees themselves can adjust the lighting or temperature in certain spots in the office. It’s also stepping away from an open floor plan office and instead having different areas for different needs. “For example, I really need to work in a place that has proper lighting where I don’t feel like I’m in an egg hatchery, and so I can control it by where I’m sitting in the space,” said Carlson. “I can have some background noise, but if there’s music playing, I’m more tuned into that than what I need to focus on.”

Carlson’s colleague, Michelle Beganskas, senior manager of workplace strategy at Ted Moudis Associates, said she agrees that acoustics are a big part of the conversation.

“If there are open environments, they are designed for a specific type of work,” said Beganskas. “No one has to complete work in an environment that they’re not able to be completely comfortable in.”

For some employers, especially smaller ones with fewer resources, the cost of an office redesign might be a barrier. However, there are still steps they can take to make their environments more inclusive of neurodivergent employees.

“There’s a lot employers can do to get started on this journey,” said Christina McCarthy, executive director of One Mind at Work, an organization that’s been in the brain health space for 30 years and helps support leaders in the business community. “It can feel pretty daunting if you’re thinking of a physical redesign. It’s a big project, a lot of money, and [can be] unclear what the net benefit will be at the end of the day.”

But having policies and procedures in place and making individual adjustments when needed are good first steps. McCarthy said that a company’s leadership also needs to make their priorities clear when it comes to this kind of inclusion.

“That leadership endorsement is really critical,” said McCarthy. “You’re going to get financial conversations and programmatic decisions to make. If leadership isn’t involved, it’s just going to be an uphill battle.”

At the end of the day, having a more intentional approach to designing offices with neurodivergent employees in mind is beneficial for everyone in the workplace because it takes a human-centered approach, stressed Russell. “That’s the bonus to it,” she said.