WTF is Pleasanteeism?

You’ve heard of presenteeism, but a new and arguably even more troubling related term is now entering the business lexicon: pleasanteeism.

On the eve of the coronavirus crisis, presenteeism — essentially, heading into the office, even if unwell, and staying there to show your face, prove diligence, impress people, but not being productive — was on the rise.

Towards the end of 2019, a Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development study indicated that 80% of U.K. employees worked when sick, which was denting the economy by £15.1 billion ($18.9 billion) every year, nearly double the cost of absenteeism.

The events since that CIPD report have entirely transformed the general attitude around in-office work, with the pressure to be present dialed down in most — but not all — industries (financial services, we’re looking at you).

So what is pleasanteeism?

As businesses chisel their hybrid-working strategies, employees are being forced back into offices. And while many relish the opportunity to converse and collaborate with colleagues in person, for some, this cheery attitude belies underlying fears about returning to work, money troubles, and mental health woes. As a result, people are suffering in silence.

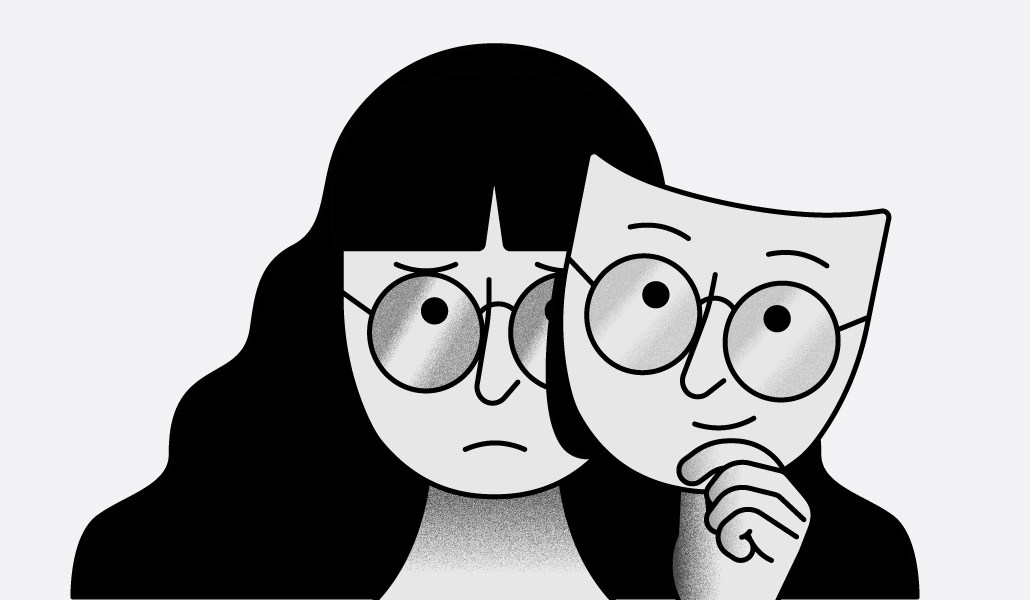

“Pleasanteeism is the sense that we always have to display our best self and show that we are OK regardless of whether we’re stressed, under too much pressure, or in need of support,” said Shaun Williams, CEO and founder of insurance firm Lime Global, who invented the term in August 2021.

“We’re all familiar with presenteeism, when someone feels like they have to physically and visibly show up at work no matter what,” he continued. “We coined the term pleasanteeism in recognition that workers are similarly having to conceal concerns and anxieties in favor of appearing productive at work.”

How bad is pleasanteeism currently?

Data shows it is getting worse. The phenomenon is rife in British workplaces, Williams warns, with Lime Global research published in February indicating that 75% of U.K. workers feel like they have to “put a brave face on at work” in front of their colleagues. Alarmingly, this was up from 51% in May 2021.

“Ongoing cost of living concerns, geopolitical uncertainty and burnout at work are fuelling a ‘pleasanteeism’ epidemic,” he continued. “At a time when mental health and well-being concerns are on the rise, unmasking pleasanteeism and encouraging people to open up and talk about their worries has never been more important.”

Mike Jones, founder of employee well-being and engagement consultancy Better Happy, believes a culture of pleasenteeism develops for two reasons. “Number one is the fear of being judged or, worse, punished for being honest about expressing poor mental health,” he said. “And, secondly, an employee having a lack of confidence in sharing and expressing their mental health concerns.”

What can employers do about pleasanteeism?

Well, data shows much more could and should be done by organizations to better support their staff. At the end of last year, workforce communication platform Firstup surveyed 23,000 people in the U.K., the U.S., Germany, Nordic and Benelux countries. Some 19% of employees noted that their employers only started showing an interest in supporting mental health since the pandemic. Almost a quarter (22%) felt that their employer has the intention to support their mental health, but they don’t feel supported. And 38% would like their bosses to create a better line of communication between executives and employees.

The first and most crucial step is to de-stigmatize poor mental health, suggests Williams. “Make it clear that it’s OK not to be OK, and open a dialogue where people can feel comfortable and confident admitting that they aren’t feeling their best without fear of repercussions,” he added.

Another vital step is to provide training to employees about positive emotional well-being. “We’ve become much better as a society at responding to poor mental health, but what we need to get better at is promoting positive mental health,” said Jones. “When people are taught through training that negative thoughts, emotions and feelings are a natural part of being a human, that it’s perfectly normal to have them and that it’s how we choose to respond to them that enables us to thrive, they are much more likely to talk about their issues and thrive.”

So communication is key?

As with most things in life, yes. If staff are suffering in silence and they are not working at their optimal level, it will be damaging to the business in the short and longer term. So it’s in leaders’ interests to encourage an open dialogue and build the mechanisms so confidential meetings are possible and greater support is offered.

Joanna Swash, group CEO of Moneypenny, a company based in the U.K. and U.S. that offers call answering and live chat services, knows the value of investing in communication. “We have a 24-hour helpline that any of our people can call if they need to talk to someone,” she said, adding that this is a completely confidential service and doesn’t affect how they are seen at work.

Swash continued: “We’re communicating with our people day in and day out. We believe what goes around comes around, so if we communicate well with our people and treat them as valued team members, they’ll provide a great communication service to our clients.”

The key point is that employers must listen to their people and encourage them to talk about any issues so they don’t rot and become more significant problems. “To do that, though, you need to have a company culture forged on trust and openness,” added Swash, “so that your employees have the right environment and feel empowered to share their thoughts and feelings.”

How can leaders themselves help?

Leaders themselves might be suffering with pleasanteeism, argues Jones. They, too, should be encouraged to be honest about how they are feeling, but it would be better for everyone if they are open, view vulnerability as a superpower rather than weakness, and lead by example.

“Managers and leaders often put pressure on themselves to be strong, to be inspirational,” he continued. “However, through never showing any weaknesses or personal struggles, they create a false narrative in their employees leading them to believe that senior people don’t ever struggle so they shouldn’t either.”