‘I was thrown off a project because I misheard’: Deaf inclusivity in the workplace still an issue

The LinkedIn profile image of culture and behavioral change consultant Simon Houghton, shows him wearing a black mask with white writing that reads: “I’m deaf. I can’t read your lips with your mask on.”

Houghton, based in Reading in the U.K., has significant hearing loss so relies heavily on lipreading when communicating – a skill which became even harder to use during the pandemic when everyone wore masks. And while the rise of virtual meetings has helped to some extent (people still turn their cameras off blocking lipreading), workplaces still don’t cater well enough to people with hidden conditions like deafness or severe hearing loss.

To boost awareness Houghton launched social enterprise WeSupportDeafAwareness during the pandemic. His message is clear: not enough is being done to support deaf workers, who make up a large chunk of the population. Consider that 1.5 billion people – almost 20% of the global population – live with a degree of hearing loss, according to the latest World Health Organization calculations.

Houghton has had to pay a heavy price for this lack of inclusivity at work. One of his worst memories he still recalls. “I was working for a big-four management consultancy firm and was thrown off a project because I misheard an action during a client meeting,” he said.

Although the incident occurred in 2001, Houghton believes workplace bias is still rife. “It would be great to think that with diversity and inclusion having such a high profile in the boardroom these days, this sort of thing wouldn’t happen in 2022, but talking to other deaf folk has confirmed that this is still an issue.”

Part of the challenge for colleagues and employers, Houghton suggests, is that deafness is a hidden disability, meaning it can be difficult to tell if someone has a hearing problem. “When someone does the wrong thing, they are often considered stupid, rather than deaf, and where speech is good, colleagues aren’t reminded that their co-worker has a hearing loss and an unconscious bias around that person forms,” he continued.

Camera-off side effects

Houghton has recently teamed up with Kevin Ashley, founder and CEO of learning management system myAko, to teach 1 million people in the U.K. about deaf awareness. “The campaign starts with education and organizations being aware of the difficulties faced by people with a hearing disability,” said Ashley. “Aside from specific training, there is now a greater understanding that mask-wearing is a significant barrier to deaf individuals’ ability to hear, and more alternatives – such as Perspex screens – are making it easier to communicate without masks.”

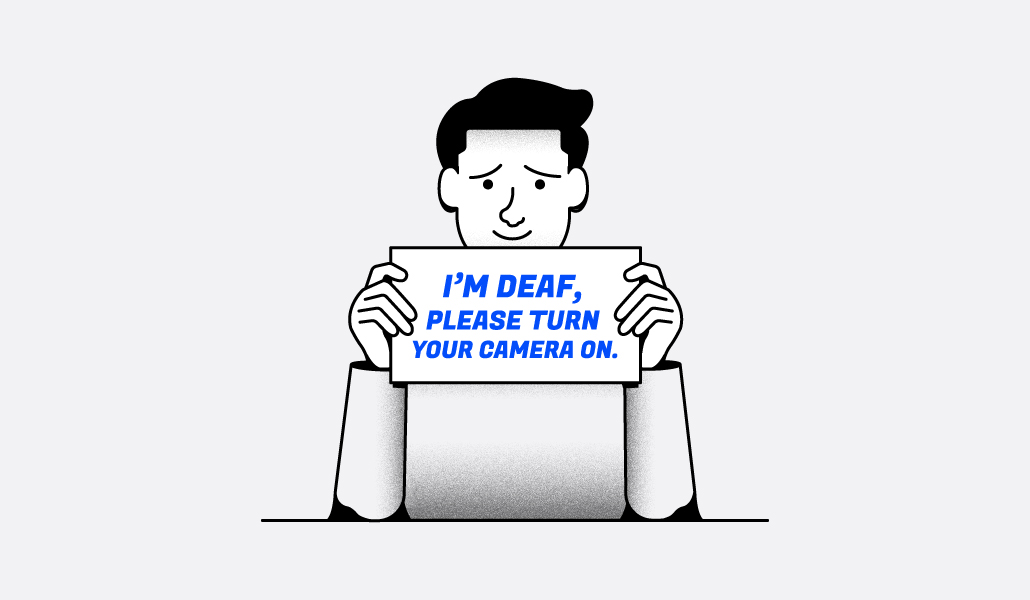

Mask-wearing aside, the shift to remote working during the coronavirus crisis was positive for deaf people, at least initially. Videoconferencing, in particular, has been an enormous benefit. “A large percentage of deaf and hard of hearing people use lipreading to understand what is being said,” said Houghton. However, colleagues would often turn off their cameras when so-called Zoom fatigue set in.

“Today, video calls are common in the hybrid working setup, but there are often a good 20-40% of people who refuse to turn their camera on,” he added. “Others will only put their camera on when speaking. This is okay, but you lose the sense of connectedness when they are not talking and can’t read their body language.”

The hard of hearing have long been marginalized, argues Dr. Joseph Murray, president of the World Federation of the Deaf. Moreover, deaf communities have endured a complicated relationship with technology. They still rue the transition from silent films to the talkies “as a moment when we went from having full access to mainstream entertainment to no access whatsoever,” he said.

Dr. Murray points out that the invention of the telephone also “shut deaf people out of communication and job opportunities” for many decades. “With this history in mind,” he added, “we are very aware that technological advances can be experienced as technological setbacks for deaf people, if access is not taken into consideration from the very beginning.”

Tech improves inclusivity

Otter.ai, a California-based software company that uses artificial intelligence to convert speech to text, has designed products to provide greater access for deaf people. For example, it launched Otter Assistant last year so people can obtain a live transcription of any Zoom, Google Meet, or Microsoft Teams meeting.

“We have heard directly from users who are deaf, hard of hearing, or have other accommodation needs, many citing Otter as a major improvement in their ability to participate and engage with confidence in business meetings,” said co-founder and CEO Sam Liang.

He points to data from Accessibility Online that shows 30% of working professionals have a disability, and 62% of those are invisible. Products like Otter Assistant allow participants to add questions or comments, assign action items, make notes or add slides to the live transcript. “We’ve heard these features give deaf and hard-of-hearing employees a great resource to contribute meaningfully, collaborate, and take more from meetings and other forms of communication than ever before,” added Liang.

Undoubtedly, tech solutions can enable greater participation for deaf workers. But now, with many companies embracing hybrid working – where employees will be split across offices and remote working – leaders have to be more inclusive or risk isolating certain employees.

“It is down to organizations to promote inclusion within their teams and to ensure they consider the needs of their struggling staff,” said Houghton. “With greater inclusion and a more psychologically safe environment, I hope that staff will feel empowered to let their colleagues know that they have a hidden disability.”